Transponders, part 2

Hello my dudes and dudettes, this is part 2 of the transponder aepic which I hope some of you might find useful in one way or another. This is where we submerge into gory details of transponders produced by Texas Instruments in the hopes of understanding how to talk to them. It should be obvious enough what data is taken from TI’s datasheets and all rights and lefts belong to The Owners and so on and so forth; if no mention is made otherwise, stuff comes from there.

OK Google, which transponder should I use for the immobilizer in the (car model here) key?

Transponder Texas Crypto 4D DST / ID67 / JMA TPX2 / Errebi TX2 / CN2, CN5 / K-JMD

OK Google, what the fudge does all this mean?

(silence of the internets)

Jokes aside (not), I now know the transponder that goes into (car model here) key is made by TI, it runs on bitcoins, it is four-dimensional, and observes the daylight saving time. No clue about the rest but some of that stuff is probably made in China.

The Texan wonder

Let me save your time by saying that whatever you google on that topic, there are several things that come up very, very often:

- TI’s very short datasheets that shed a little light on what these might be, albeit strangely not mentioning the fourth dimension anywhere;

- Three papers (“Security Analysis of a Cryptographically-Enabled RFID Device” by Bono et al, “Fast, Furious and Insecure:Passive Keyless Entry and Start Systems in Modern Supercars” by Wouters et al, “Dismantling DST80-based Immobiliser Systems” again by Wouters et al) on breaking the cryptographic algorithms inside and outside of them;

- A bunch of forum posts with people begging to help them put transponder info into an immobilizer EEPROM dump; and

- A bajillion of web sites trying to sell them transponders to you, often hardly mentioning anything but “ID70” or something.

Of these, the first two contain some useful information, whereas the latter ones do not. Oh, and I also learned that DST means “digital signature transponder”, not “daylight saving time”!

Luckily, I have read all of the above so you don’t have to, and I’m going to tell you all the important bits. From the datasheet department, we have:

- TI SCBU020 “Texas Instruments Registration and Identification System” aka TIRIS, talking about probably the very first batch of transponder products from TI;

- TI SCBU037 “RI-TRP-R9BK, RI-TRP-W9WK Wedge Transponder Reference Guide”, talking about a more modern version of the same;

- TI “RI-TRP-B9WK-xx Datasheet”, a flimsy one-pager laying out what little information TI decided to surrender on DST40 transponders;

- TI SCBS881E “TMS3705 Transponder Base Station IC”, describing what looks to be a complete reader solution sans the antenna and a few bits and pieces;

This was my initial batch of things to wade through. Not too much, really, but that’s expected for anything remotely related to the automotive world.

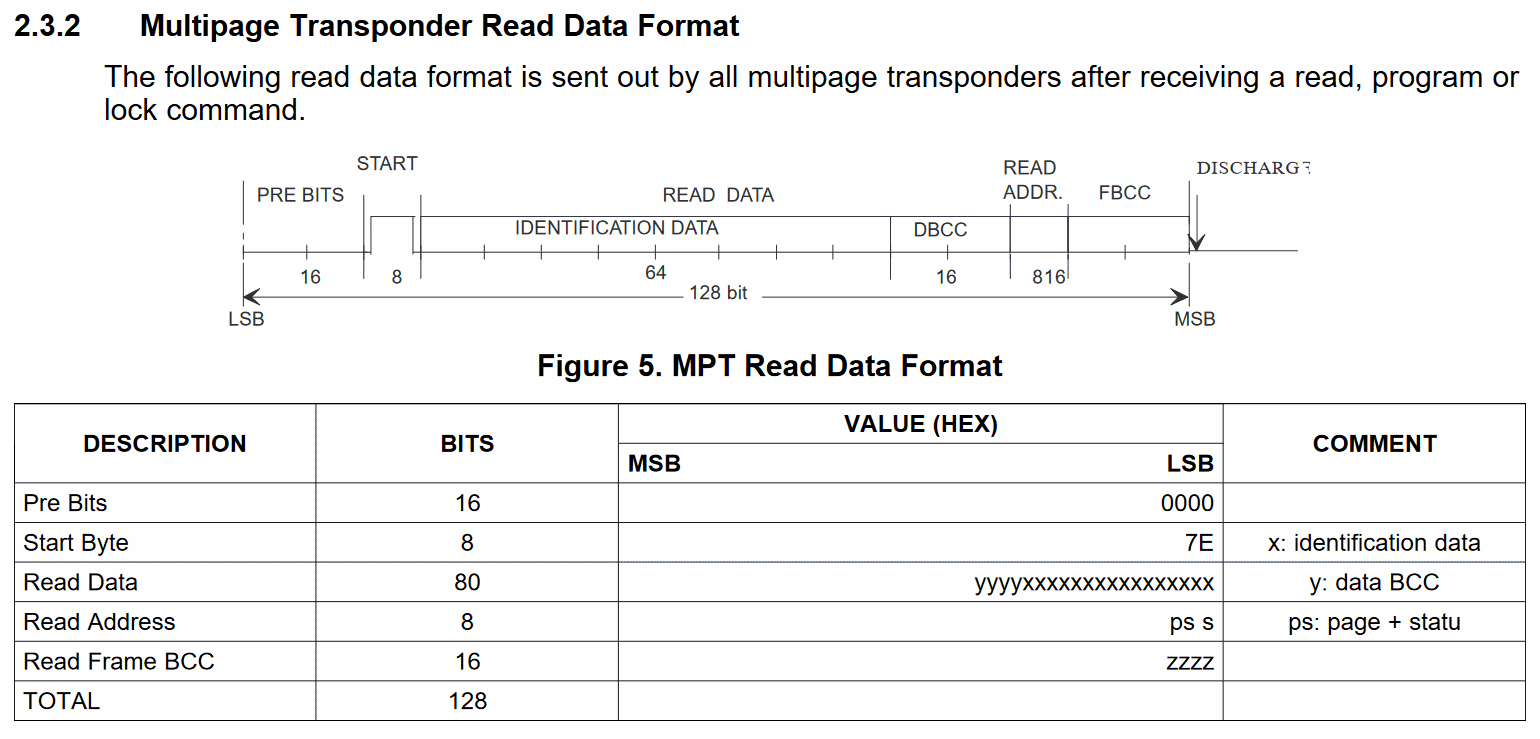

Reading through the first two, there are a couple things they tend to say again and again; with any luck, these stay the same for all of the transponders made by TI. First and foremost, they talk about the format of data returned by the transponder itself. This goes like this:

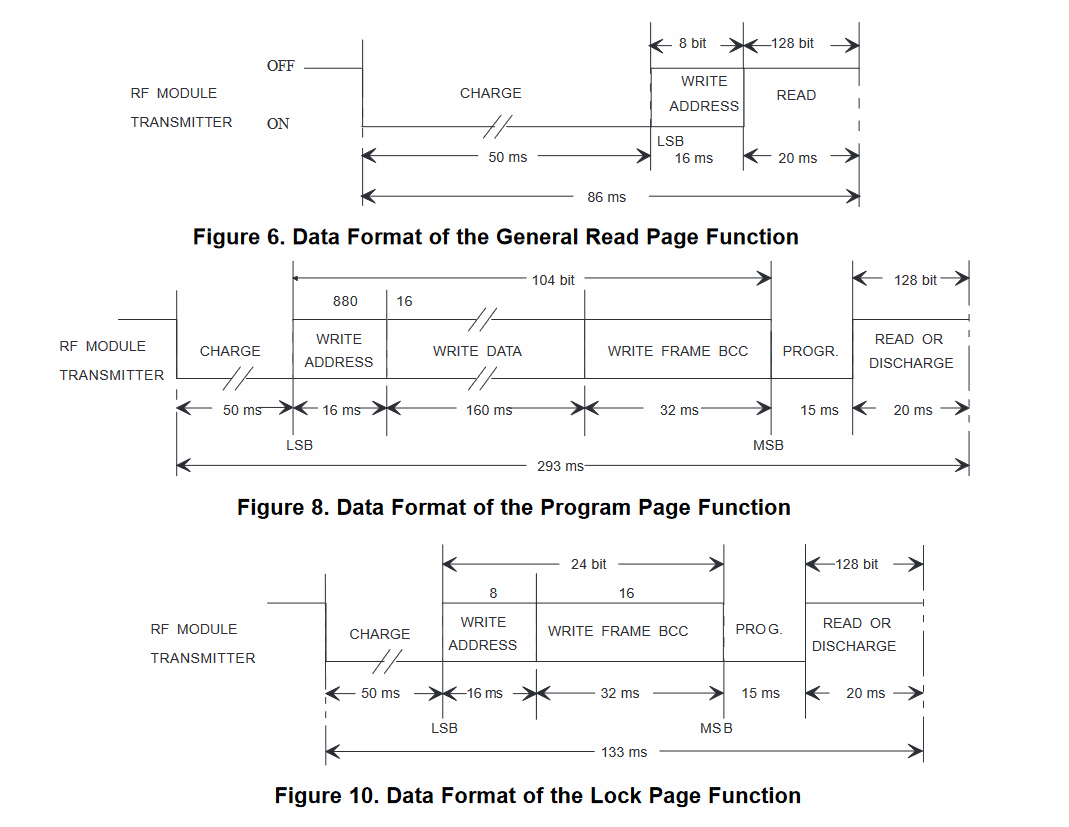

Keep in mind, this is not necessarily what would actually be returned by any other transponder than what’s described, but engineers typically stick to their choices for more than one project and the format might be similar enough. Kinda implied in the picture and also highlighted in the text is that all data is transferred LSB first; this might come in handy at some point later. The datasheets also note the transponders have “pages” which can be read, programmed, and locked to prevent reprogramming as well as sketch out the approximate frame format for that. I’ll put it here for future reference:

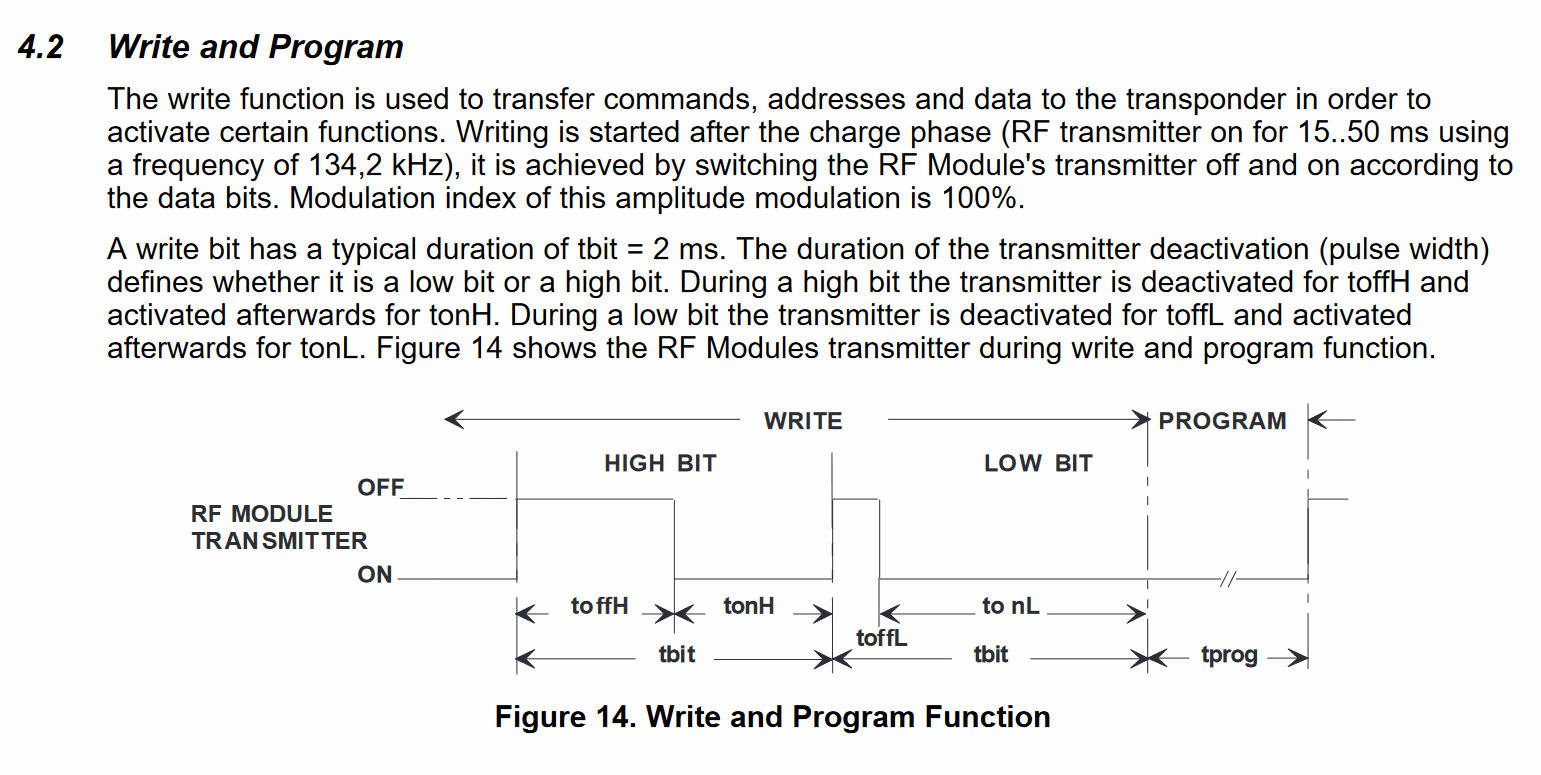

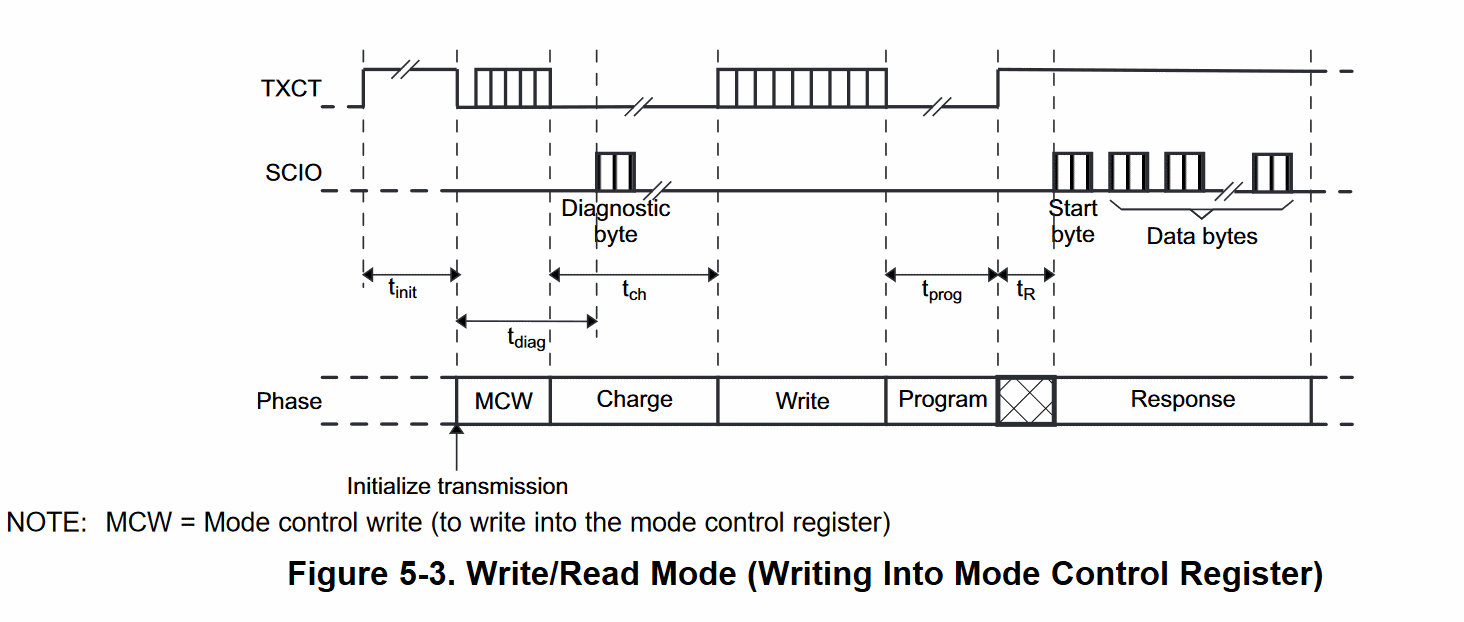

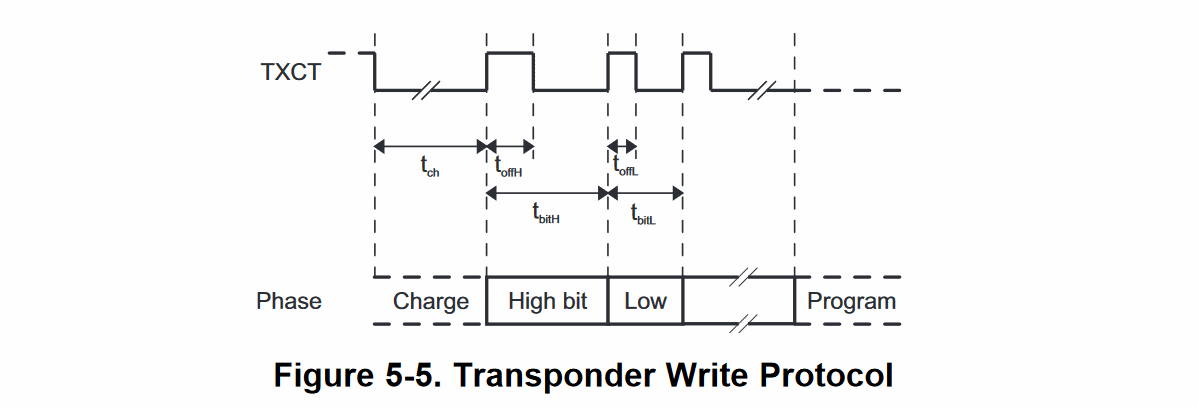

…along with a nice diagram showing how we’re actually supposed to transmit stuff to the transponder:

Oddly enough, no actual values for toffL and toffH etc are provided in SCBU020. This gap is filled by SCBU037, citing 0.3 and 1.0 milliseconds for “low” and “high” bits, overall duration being 2 ms for both. Maybe it will work with more than these specific devices? We won’t know if we don’t try.

Oh, and they also mention that all the BCC things are actually CRC16-CCITT, without going into much detail. Which is too bad, as one can flip the CRC pancake in many, many ways.

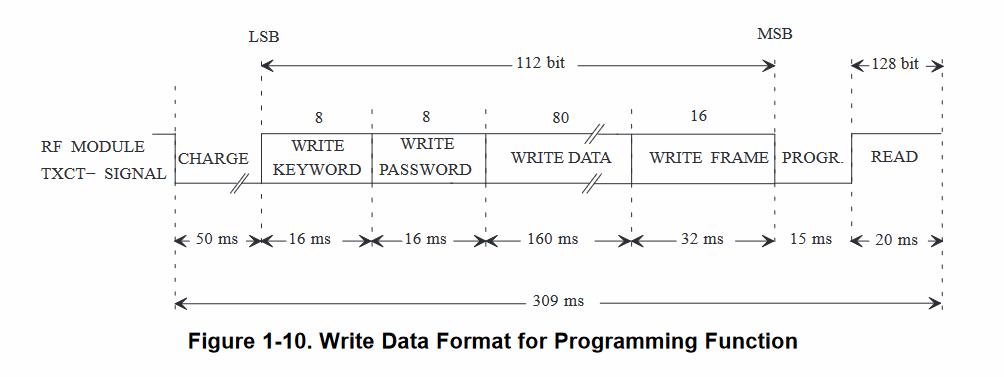

SCBU037 also shows a nice change concerning the programming function, namely including a “write password” on this diagram which is mentioned nowhere else in the document. What’s the password? My guess is no better than yours, and googling does not bring any relief for the curiosity itch.

And that’s basically all she wrote in them datasheets. I won’t bore you with details on the modulation and especially testing methodologies. The actual RF level stuff should be done by this “Transponder Base Station IC” thingamajig, the TMS3705, or so I hope.

Now the “datasheet” on RI-TRP-B9WK, if you can call it that, highlights an important detail on memory page contents of DST40 transponders:

- Page 1, 8 bits, is the “password”, failing to mention what this password is for – but hey, we’ve heard about this before somewhere?

- Page 2, 8 bits, is “Identification ID”, whatever that means;

- Page 3, 32 bits, is the serial number and manufacturer code; and

- Page 4, 40 bits, is the DST40 key.

Oh, and they also tell me the challenge is 40 bits and the response is the serial number + response + CRC again. Fin. It’s… a lot, but not much at the same time. Oh, and no mention how should I cook these fresh challenge bits I just generated?

All your base stations are… you know the rest

The TMS3705 datasheet adds a few more touches to the picture. The chip itself seems to be the popular offering from TI for designers to build transponder readers, and the one with a somewhat verbose datasheet to boot. Apart from the analog-y bits like the antenna, there are two digital pins sticking out – TXCT being its input and SCIO being its UART-like output, where it repeats loud and clear whatever the transponder whispers into its antenna. The TXCT pin is the lever controlling the magical electromagnetic field generation.

The datasheet confirms and validates what we knew before from transponder datasheets while also showing how to actually make the chip do that by manipulating that TXCT pin.

See how this matches with the above diagrams for the transponders? That’s good, very good. What is curious, though, is how they chose to picture the bit writes:

Astute readers might notice how they delibarately draw tbitH != tbitL. This might or might not suggest something, but for now let’s just pen it down.

The last important bit is, the chip will listen for about 20 ms for transponder’s response and then go back home. Aaaaand that was about it, I think? I hoped for more juicy bits, to be honest, but at least it seems like a start. The bottom line is, if we tickle the TXCT pin in the right way, transponder bits will arrive from the SCIO pin for us to peruse.

Papers, please!

The papers mostly go about what DST40 and DST80 are, the particularities of these algorithms, and give enough information to implement them. Kinda.

The Bono paper explores the DST40 algorithm and also goes into a wee bit detail on how the actual authentication algorithm is invoked: you send it a “8-bit opcode followed by a 40-bit challenge.” The opcode “indicates the type of request being made (in this case an authentication request)”. Unfortunately, the team decided not to go into it any further than that, so what exactly do we send in remains a mystery to this day. But not for too long!

The Lennert papers kinda build on the Bono paper and others but explore the DST80 instead. They also reveal the existence of page 30, which stores “configuration”, but do not go into detail on that either. They note transponders can be switched between DST40 and DST80 but do not specify which bit controls that. For me, this paper is for reference only as I’m mostly interested in DST40 anyway.

Again, a lot and not much at the same time.

Ze end

I don’t know about you three who read the post until this point, but I feel like I am ready to get my hands dirty. All we need is blood a device to talk to and a ready-made reader thingamajig so we don’t have to do all the RF bits. After all, the best work is work that’s done for you by someone else already. Come back for part three (oh wow) where we’ll touch this boi in many inappropriate ways and maybe read some bits or something!

Until then, love, peace, and bubblegum!